Short summary

Since 1970, enrollment in tertiary education has increased by a factor of 3.4 in OECD countries, with further growth remaining a key political discussion. For instance, the European Union’s goal for 2030 is that “The share of 25–34 year-olds with tertiary educational attainment should be at least 45%.” The UK tertiary education expansion, where the share of 17–30 year-olds in higher education rose from 5% in 1960 to 43% in 2007 and kept increasing afterwards, is an ideal case to study the possible implications of expanding tertiary education. We find that the UK expansion led to the selection into college of progressively less talented students from advantaged backgrounds. The lesson is that unless tertiary education expansions are explicitly and effectively targeted towards the talented poor, it is likely that only low-ability, advantaged children will be selected into college.

Key Findings

- In the UK, the cognitive ability of students selected into college declined by about 13% of a standard deviation between the 1960s and the early 2000s, even if a large reserve of talented potential college students existed.

- The share of college graduates coming from the top tercile of the cognitive ability and family disadvantage distributions, i.e., the talented poor, declined from 12.8% to 10.4%.

- On the contrary, the share of college graduates coming from the bottom tercile of these distributions, i.e., the untalented rich, increased from 5% to 7%.

- Counterfactual policies were feasible that would have achieved the dual goal of increasing college graduates’ cognitive ability while improving tertiary education opportunities for the disadvantaged.

Relevance Today

The prevailing consensus in the policy debate of most countries is that further tertiary education expansions are necessary, and high targets are set accordingly. These targets are set without mention of the cognitive skills that students selected into college ought to have. While such neglect may be inspired by equity aspirations, the key lesson conveyed by our analysis is that it is possible to take these skills into account and reconcile graduates’ quality with better college opportunities for the disadvantaged. In other words, it is possible to design tertiary education expansions that are both ability-enhancing and disadvantage-mitigating. Such a design, rather than the expansion per se, should be at center stage in the policy discussion.

Reference: Paper reference: RFBerlin Discussion paper N. 75/25, forthcoming in the Review of Economic Studies

Research summary

University access has greatly expanded during the past decades, and further growth figures prominently in political agendas. The enlargement of tertiary education enacted in the UK following the influential 1963 Robbins Report provides an ideal case study to draw policy lessons. We find that this expansion is associated with a decline in the average cognitive ability of graduates and in a flat college wage premium across cohorts, despite education-based technical progress. Those who benefited from the implemented expansionary policy are primarily the relatively less talented students from advantaged socioeconomic backgrounds. Thus, this policy was unfit to reach the existing “reserves of untapped ability in the poorer sections of the community” that Robbins had in mind. Appropriate counterfactual policies were feasible that would have achieved the dual goal of increasing college graduates’ cognitive ability while improving tertiary education opportunities for the disadvantaged.

Enrollment in tertiary education increased by a factor of 3.4 in OECD countries since 1970 (UNESCO Statistics, 2021), and further expansion figures prominently in political agendas. For example, the European Union’s goal for 2030 is that “The share of 25-34 year-olds with tertiary educational attainment should be at least 45%” (Council of the EU, 2021). However, we do not know much about the consequences of such historical and planned expansion processes in terms of cognitive ability and socioeconomic background of the students selected into college, even though these consequences should be at the center stage in the policy debate on education.

The enlargement of university access enacted in the UK following the 1963 Robbins Report provides an ideal case study to address these issues and to draw policy lessons. In the UK, the share of 17-30 year-olds enrolled in higher education rose from about 5% in 1960 to 43% in 2007 (Chowdry et al., 2013), an increase that mimics the one that had already taken place in the US (Goldin and Katz, 2008) and that would later occur in other OECD countries (Schofer and Meyer, 2005; Meyer and Schofer, 2007). In our paper “College, cognitive ability, and socioeconomic disadvantage: policy lessons from the UK in 1960-2004” (RFBerlin Discussion Paper N. 75/25, forthcoming in The Review of Economic Studies), we study the UK experience to evaluate the possible consequences of the ambitious targets for tertiary education that are currently set in Europe and elsewhere.

The “Robbins Report” and the intellectual origin of the UK expansion

The intellectual origin of the UK expansion is the Robbins Report (Robbins, 1963). Contrary to more recent policy blueprints, this Report should be credited for basing its recommendations on the assessment of what would happen in the future to the skills of college graduates and non-graduates. The Report claimed the existence of large “reserves of untapped ability [that] may be greatest in the poorer sections of the community” (p. 53) and thus recommended that “all young persons qualified by ability and attainment to pursue a full-time course in higher education should have the opportunity to do so.” (p. 49). According to the Report, “fears that expansion would lead to a lowering of the average ability of students in higher education [were] unfounded.” (p. 53). These claims have not been adequately investigated, in part because of the lack of data sets containing cognitive ability measures. An upside of our main data source (Understanding Society: The UK household longitudinal study) is that it allows us to construct a measure of general cognitive ability, in addition to predetermined individual measures of socioeconomic disadvantage.

The consequence of the UK higher education expansion

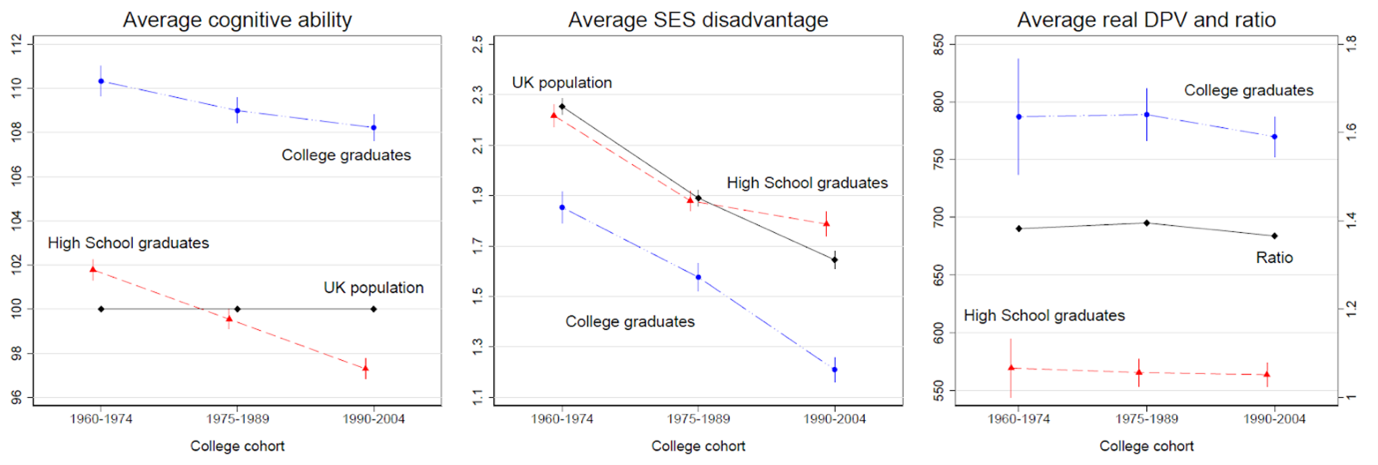

Our most novel result (left panel of Figure 1) is that the average cognitive ability of college graduates declined by about 13% of a standard deviation between the 1960s and the 1990s. Non-graduates’ average ability also declined, indicating that students who attained a college degree in the 1990s (and who would not have attained it in the 1960s) were more able than the average high school graduate of the 1960s, yet less able than the average college graduate of the same period. As for the socioeconomic status of college graduates (central panel), it has improved relative to that of the non-graduates, which indicates an increasingly unequal access to tertiary education by family background. Finally, we find that these effects are associated with a flat college premium in terms of the discounted present value of earnings (right panel), despite the education-biased technological progress that exerted its effects during the same period.

Figure 1. Consequences of the UK tertiary education expansion

Notes: A college cohort is a group of individuals in actual (for graduates) or potential (for non-graduates) college attendance age, labeled by year of birth plus 20 (so, for example, the 1960-74 cohort is composed of subjects born between 1940 and 1954). An individual’s cognitive ability is measured by the first principal component of 14 cognitive ability variables (scores in tests of episodic memory, working memory, fluid reasoning, semantic fluency, and problem solving/numeracy, and whether help was received during the test); this measure is normalized to have a mean of 100 and a SD of 15 in each college cohort. An individual’s disadvantage is measured by the first principal component of 13 socio-economic variables that affect a student possibility to study with profit (years of schooling of a respondent's parents, six dummies for whether a respondent's father or mother were employed when the respondent was 14, whether a respondent was not living with her/his father or mother at the age or 14, and whether a respondent's father or mother were deceased when the respondent was 14); the figure shows the average of this measure by graduation status relative to the population in each college cohort. Average real present discounted values of earnings are expressed in thousands of real GBP (2015 prices). Data sources: Understanding Society.

These outcomes for the UK were the result of an increase in the number of graduates that was not ability-enhancing in the sense of not being targeted to bring into college the most able students who otherwise would not have attended it. Such an increase has been achieved by reducing non-tuition costs and by lowering qualification barriers at entry into college. Therefore, although the untapped ability envisioned by Robbins did exist, the higher education policy that eventually prevailed was unfit to draw this ability into universities and ended up favoring primarily low-ability students from advantaged families. Our policy simulations, based on a rigorous estimation of structural model parameters, suggest that alternative policies could have achieved the Robbins Report’s progressive goals. For example, an expansion of tertiary education opportunities specifically targeted to the most able students, with additional aid to the disadvantaged among them.

We do not necessarily suggest that university admission should be made more dependent on test scores reflecting academic performance at the end of high school (e.g., A-level grades in the UK). Whether a student has obtained these qualifications and how high he or she scored may reflect selection based on the family’s socioeconomic status occurring earlier in life. For this reason, secondary education policies aimed at improving the attainment of talented teenagers from disadvantaged families should be combined with admission policies that feature cognitive ability assessments. For example, low-variance (e.g., repeated over time) cognitive ability tests that reflect students’ talent independently of their socioeconomic advantage or disadvantage. Proposing such measures is beyond the scope of our analysis, but a variety of them already exist. Their specific definition should be left to experts. Our evidence clearly indicates that this is the way to follow if one wishes to increase the number of graduates and their quality, while also providing equality of opportunities.

A lower cognitive ability of college graduates can hardly be characterized as desirable

Although we eschew the difficult question of which social welfare function should be used to determine the optimal number of college graduates, we claim that a lower average cognitive ability of college graduates can hardly be characterized as a desirable outcome. In our model, the reason is that a higher ability is associated (ceteris paribus) with a lower study effort cost, which implies a social welfare gain from a more able graduate workforce relative to a less able one of the same size. To put it differently, it is more costly to turn a low-ability student into a good medical doctor or into a good engineer, and maybe it is not even possible.

A richer model may consider other reasons. For example, universities have a double role in society: providing higher education but also supporting basic research at an advanced level in all fields, a task that is facilitated by higher cognitive ability. Thus, the consequences of a decline in the average ability of graduates are going to be far-reaching, particularly if there is reluctance to allow the tertiary education institutions to be more selective in their acceptance. The Robbins Report clearly mentions the lack of a depressing effect on graduates’ average ability as a condition that justifies an expansion. Surprisingly, such a concern is absent in Council of the EU (2021), which sets the goal of at least 45% of graduates in the EU by 2030. It is not even clear how this specific threshold has been chosen.

Key lesson

We have introduced into the analysis of higher education policy the systematic consideration of individuals’ cognitive ability, in addition to conventional measures of socioeconomic disadvantage. The notion of ability as a scarce resource to be allocated across different education levels is an important consideration in the rich analysis of the Robbins (1963) Report. Such consideration and analysis are instead conspicuously absent in the current debate. While such neglect may be inspired by equity aspirations, the key lesson conveyed by our analysis is that it is possible to reconcile graduates’ quality with better college opportunities for the disadvantaged in the design of tertiary education expansions. These expansions would be both ability-enhancing and disadvantage-mitigating.

References

UNESCO Statistics (2021): “School enrollment, tertiary (% gross),” retrieved from World Bank Open Data, https://data.worldbank.org/indicator/SE.TER.ENRR.

Council of the EU (2021): “Council Resolution on a strategic framework for European cooperation in education and training towards the European Education Area and beyond (2021-2030),” Resolution 2021/C 66/01, Official Journal of the European Union, 64.

Chowdry, H., C. Crawford, L. Dearden, A. Goodman, and A. Vignoles (2013): “Widening participation in higher education: analysis using linked administrative data,” Journal of the Royal Statistical Society: Series A (Statistics in Society), 176, 431–457.

Goldin, C. and L. F. Katz (2008): The Race between Education and Technology, Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press.

Schofer, E. and J. W. Meyer (2005): “The Worldwide Expansion of Higher Education in the Twentieth Century,” American Sociological Review, 70, 898–920.

Meyer, J. W. and E. Schofer (2007): “The University in Europe and the World: Twentieth Century Expansion,” Transcript verlag, Towards a Multyversity. Universities between Global Trends and National Traditions.

Robbins, L. (1963): “Higher Education: Report of the Committee Appointed by the Prime Min- ister Under the Chairmanship of Lord Robbins, 1961-63”.

Disclaimer

The opinions and views expressed in this publication are those of the author(s) and do not necessarily reflect those of the ROCKWOOL Foundation Berlin (RFBerlin). While research disseminated through this series may address policy-relevant topics, RFBerlin, as an independent research institute, does not take institutional policy positions.

Publications in the RFBerlin Research Insights series may represent preliminary or ongoing work that has not been peer-reviewed. Readers are advised to consider the provisional nature of such research when citing or applying its findings.

These publications aim to make scientific work accessible to a broader audience and to encourage informed, research-based discussion. All materials are provided by the respective authors, who bear responsibility for appropriate attribution and rights clearance. While every effort has been made to ensure accuracy and proper acknowledgment, RFBerlin welcomes notifications of any concerns regarding authorship, citation, or intellectual property rights. Please contact RFBerlin to request corrections if needed.

Use of these materials for the development or training of artificial intelligence systems is strictly prohibited.