Short summary

Regional inequalities remain a central issue in public and policy debates. In Germany, average full-time wages in the richest 10% of counties are more than 40% higher than those in the poorest 10%. This raises core questions: Where do such disparities originate? How persistent are they? And what policies can reduce them?

A new study traces these inequalities back to the introduction of a transformative technology: the steam engine. Much like AI today, the steam engine was among the most disruptive technologies in the 19th century. While the long-term effects of AI remain uncertain, history provides guidance: German regions that had more steam engines per worker in 1875 have higher wages, a more skilled labor force, and greater firm productivity today. They also show greater occupational diversity and sustained innovation over time.

These findings are consistent with theories of technology–skill complementarity (where new technologies raise the demand for skills) and directed technical change (where firms orient innovation toward exploiting those higher skills), pointing to a persistent, self-reinforcing dynamic between technological progress and human-capital development.

Authors

- Sascha O. Becker (RFBerlin, Warwick University)

- Christian Dustmann (RFBerlin, UCL)

- Hyejin Ku (RFBerlin, UCL)

Steam was the transformative technology of the 19th century. Today, AI or digital technologies may play the same role. This study shows that more active adoption of a disruptive technology can reshape regional fortunes for more than a century.

Key Findings

- Higher long-run wages in regions with higher steam engine density: Compared to regions with an average adoption rate of 6.64 steam engines per 1,000 workers in 1875, regions that were in the top 10% steam engine intensity (13.13 steam engines per 1,000 workers) have 4.59% higher average wages in modern day Germany (1975-2019). This wage premium holds after accounting for worker demographics, historical industry mix, and geography.

- Greater educational attainment and higher firm productivity: These regions have also a larger share of tertiary-educated and technically skilled workers 150 years later, as well as more productive firms. The study finds that nearly 50% of the steam engine-related wage premium is explained by having more productive firms in these regions.

- Innovation and technological diversity: Regions with more steam engines per worker in 1875 registered significantly more patents, historically (1877-1918) and in recent decades (1980–2014), and show greater technological diversity in their innovations.

- Occupational diversity: Regions with more steam engines per worker in 1875 exhibit greater occupational diversity today, both in overall economy and within the manufacturing sector

“Steam power didn’t just fuel factories, it reshaped the technology and skill development of entire regions for generations. The lesson for today is clear: early adoption of transformative technologies like AI can have long-lasting consequences.”

— Christian Dustmann

📄 Based on RFBerlin Discussion Paper 13/26: Becker, Dustmann & Ku (2025) “The Virtuous Cycle Between Skills and Technology”

A central question in economics is how new technologies shape labor markets and, in turn, how these changes influence innovation and long-run growth (Autor et al., 2003; Katz & Margo, 2014). With today’s rapid advances in automation, digitalization, and artificial intelligence, this issue has gained renewed urgency (Brynjolfsson & McAfee, 2014; Autor, 2015; Acemoglu & Restrepo, 2018).

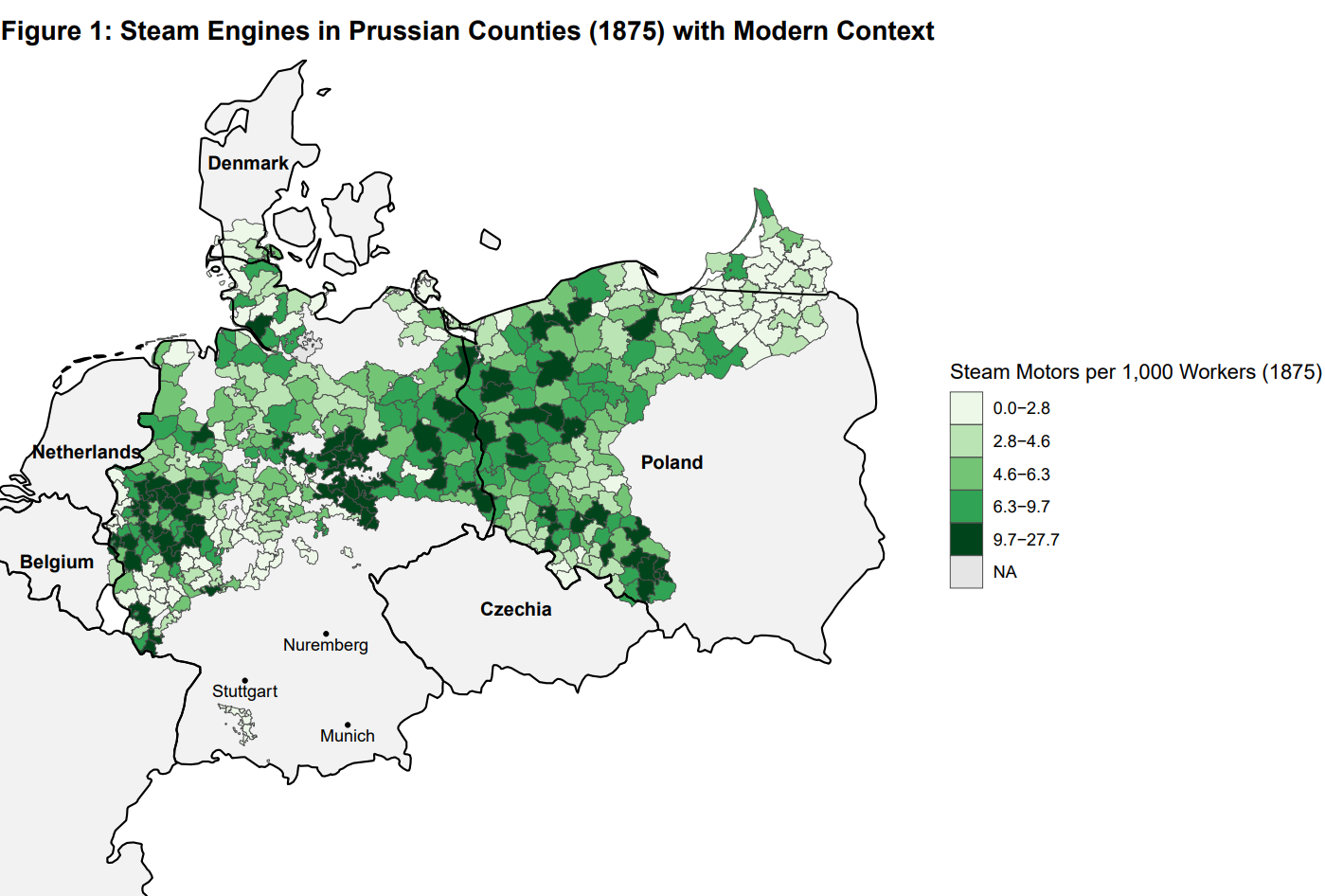

Our study (Becker, Dustmann & Ku, 2025) takes a historical perspective. We examine one of the most transformative technologies of the past: the steam engine. Unlike water or wind power, steam provided a reliable, scalable, and geographically flexible source of energy that reshaped industrial production across 19th-century Germany (Crafts, 2004). By linking digitized census records of steam adoption in 1875 to German social security data (1975–2019), firm productivity measures, and historical as well as modern patent data, we investigate how steam engine adoption influenced regional outcomes over more than a century. Figure 1 shows the number of steam engines per 1,000 workers in 1875 across Prussia.

Notes: This figure shows the spatial distribution of steam engines per 1000 workers in 1875. Data on steam engines are available at the level of year 1871 Prussian counties. The figure also shows the boundary of modern Germany 2019.

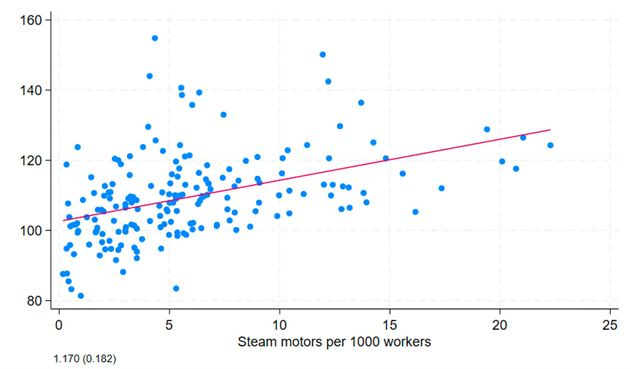

The results are striking. Regions with higher steam engine density in 1875 have persistently higher wages today: a one standard deviation (4.6 steam engines per 1,000 workers) increase in steam adoption is associated with 2.3–3.7% higher wages today. This relationship can also be seen in Figure 2 which shows the number of steam engines per 1,000 workers on the X-axis and mean wages in 2015 on the y-axis.

Notes: This figure shows the relation between steam engines per 1000 workers in 1875 Prussia and the mean wages in West Germany in 2015.

This effect remains robust after controlling for demographics, industrial structure, and geography. Importantly, nearly half of the steam-related wage premium reflects the presence of more productive firms in these regions, consistent with the role of firms in determining wage inequality (Card, Heining & Kline, 2013).

We also find strong evidence of human capital accumulation. Steam-intensive regions have larger shares of tertiary-educated workers today. These regions also exhibit greater occupational diversity in both overall economy and within manufacturing sectors.

The innovation record further reinforces this view. Regions that adopted steam power early produced more patents historically (1877–1918) and in recent decades (1980–2014). These regions also exhibited more diverse technologies in innovations.

This supports theories of technology–skill complementarity, which argue that new technologies raise the demand for skills, encouraging investment in education and sustaining innovation (Goldin & Katz, 1998, 2009).

To establish causality, we use proximity to coal deposits as an instrument for steam adoption. Coal predicted steam use but was unrelated to pre-industrial prosperity or human capital (de Pleijt et al., 2020; Fernihough & O’Rourke, 2021). This analysis confirms that steam adoption itself triggered the long-run cycle of wages, skills, and innovation.

Implications

Taken together, these findings provide new evidence for the theories of directed technical change (Acemoglu, 1998, 2002) and technology–skill complementarity (Goldin & Katz, 1998, 2009). They show that early adoption of transformative technologies can set regions on self-reinforcing growth paths, shaping their fortunes for generations. They also suggest that technological innovation, as transformative as the steam engine, can lead to lasting economic advantage, reflected by long term differences in average wages, educational achievements, and firm productivity.

As we stand on the brink of another technological revolution, driven by AI and digital innovation, these historical lessons suggest that early adoption may once again determine which regions and countries capture the long-run benefits of technological change.

References

Acemoglu, Daron. 1998. “Why Do New Technologies Complement Skills? Directed Technical Change and Wage Inequality.” Quarterly Journal of Economics, 113(4): 1055–1089.

Acemoglu, Daron. 2002. “Directed Technical Change.” Review of Economic Studies, 69(4): 781–809.

Acemoglu, Daron, and Pascual Restrepo. 2018. “The Race between Man and Machine.” American Economic Review, 108(6): 1488–1542.

Autor, David. 2015. “Why Are There Still So Many Jobs?” Journal of Economic Perspectives, 29(3): 3–30.

Autor, David H., Frank Levy, and Richard J. Murnane. 2003. “The Skill Content of Recent Technological Change: An Empirical Exploration.” Quarterly Journal of Economics, 118(4): 1279–1333.

Becker, Sascha O., Christian Dustmann, and Hyejin Ku. 2025. “The Virtuous Cycle Between Skills and Technology.” RFBerlin Discussion Paper 13/26.

Brynjolfsson, Erik, and Andrew McAfee. 2014. The Second Machine Age. New York: W.W. Norton.

Card, David, Jörg Heining, and Patrick Kline. 2013. “Workplace Heterogeneity and the Rise of West German Wage Inequality.” Quarterly Journal of Economics, 128(3): 967–1015.

Crafts, Nicholas. 2004. “Steam as a General Purpose Technology.” Economic Journal, 114(495): 338–351.

de Pleijt, Alexandra, Alessandro Nuvolari, and Jacob Weisdorf. 2020. “Human Capital Formation During the First Industrial Revolution: Evidence from the Use of Steam Engines.” Journal of the European Economic Association, 18(2): 829–889.

Fernihough, Alan, and Kevin Hjortshøj O’Rourke. 2021. “Coal and the European Industrial Revolution.” Economic Journal, 131(635): 1135–1149.

Goldin, Claudia, and Lawrence F. Katz. 1998. “The Origins of Technology-Skill Complementarity.” Quarterly Journal of Economics 113(3): 693-732.

Goldin, Claudia, and Lawrence F. Katz. 2009. The Race between Education and Technology. Harvard University Press.

Katz, Lawrence F., and Robert A. Margo. 2014. “Technical Change and the Relative Demand for Skilled Labor: The United States in Historical Perspective.” In Human Capital in History: The American Record, edited by Leah Platt Boustan, Carola Frydman, and Robert A. Margo. Chicago: University of Chicago Press, pp. 15–58.

Disclaimer

The opinions and views expressed in this publication are those of the author(s) and do not necessarily reflect those of the ROCKWOOL Foundation Berlin (RFBerlin). While research disseminated through this series may address policy-relevant topics, RFBerlin, as an independent research institute, does not take institutional policy positions. Publications in the RFBerlin Research Insights series may represent preliminary or ongoing work that has not been peer-reviewed. Readers are advised to consider the provisional nature of such research when citing or applying its findings.These publications aim to make scientific work accessible to a broader audience and to encourage informed, research-based discussion. All materials are provided by the respective authors, who bear responsibility for appropriate attribution and rights clearance. While every effort has been made to ensure accuracy and proper acknowledgment, RFBerlin welcomes notifications of any concerns regarding authorship, citation, or intellectual property rights. Please contact RFBerlin to request corrections if needed. Use of these materials for the development or training of artificial intelligence systems is strictly prohibited.