Short summary

Immigration affects regions more than individual workers

How does immigration affect jobs and wages? Public debates often conflate regional labour market outcomes with the experiences of individual workers. Analyzing a German cross-border commuting policy after the fall of the Berlin Wall, when Czech workers could work in German border districts without living there, this paper shows that immigration significantly reduced native employment in these regions. At the same time, the risk of job loss for existing native workers remained low. On the other hand, although average regional wages appear unaffected, native workers who remain employed experience modest wage declines. Thus, the effects of immigration on “places” and “people” may differ considerably.

Key findings

- A one-percentage-point increase in the immigrant employment share reduces regional native employment by 0.87% after three years.

- For workers employed at the time of immigration, the probability of job loss rises by only 0.14 percentage points, and the effect disappears after five years.

- Regional average wages remain flat, but continuously employed natives experience a wage decline of about 0.19%.

- The negative wage- and employment effects fall disproportionately on older workers and those not employed at the time of the immigration shock.

- Contrary to some interpretations, there is no evidence that native workers move from lower-skilled, repetitive jobs to higher-skilled, more complex roles. Instead, immigration discourages workers who might have taken these lower-skilled jobs from entering the affected labour market.

- Immigration, however, encourages young labour market entrants to enrol in apprenticeship training rather than entering the labour market directly.

Relevance Today

The findings show that the effects of immigration on places (local labour markets) and people can differ greatly. Policymakers who rely solely on regional averages can be misled about how immigration affects individual workers and which groups bear the costs.

Paper Reference

Based on The Effects of Immigration on Places and People – Identification and Interpretation, RFBerlin Discussion Paper No 86/25 (2025); forthcoming Journal of Labor Economics.

Research Summary

The impact of immigration on the jobs and wages of native workers is a central concern in public and political debates worldwide. Yet the economic literature offers a wide range of estimates, often fuelling controversy rather than resolving it (Dustmann et al. 2016, National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine 2017, Nedoncelle et al. 2025). In our recent study (Dustmann et al. 2025), we argue that part of this divergence stems from a fundamental measurement issue: standard approaches often conflate the effects on places with the effects on people. By using longitudinal data that track individual workers in Germany over time, we show that the impact on workers employed at the time of immigration often differs from regional figures.

The problem with comparing places

Most studies employ an approach that utilizes repeated cross-sectional data to compare labour market outcomes across regions with varying levels of immigration. While intuitive, this method captures a combined effect that bundles together several distinct and often offsetting mechanisms. Take employment. A decline in native employment following an immigration influx could mean two very different things. It could mean that native workers who were already employed are losing their jobs, which we call a ‘displacement effect’. However, it could also mean that employed workers are largely unaffected, but fewer new native workers enter the local labour market, or young people choose not to take up jobs there – an effect we term ‘crowding-out’. These scenarios have very different policy implications but cannot be disentangled using regional data alone. Wage analysis faces a similar issue. Immigration may depress wages through increased labour supply (the ‘pure’ wage effect). But regional average wages also depend on workforce composition (Card 2001, Bratsberg and Raaum 2012, Borjas and Edo 2025). If lower-wage natives exit employment or move away, the average wage of the remaining, more productive workers may rise, masking the true impact on those who stay.

A natural experiment on the German border

To separate these effects, we study a unique policy experiment following the fall of the Berlin Wall. Czech workers were allowed to commute to German border districts for work without the right to reside there. This created a pure labour supply shock, as the commuters earned wages in Germany but consumed mostly at home (see Dustmann et al. 2017). Using longitudinal social security data covering the entire workforce, we track individual careers before and after the shock. This allows us to distinguish effects on workers (‘people’) from aggregate effects on the places. We use distance from the border as an instrumental variable to address endogenous settlement patterns toward economically stronger regions.

Employment: Crowding-out rather than displacement

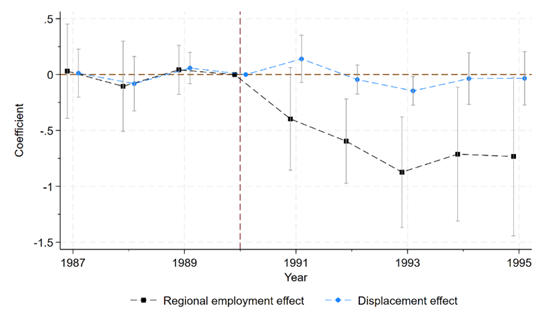

Figure 1 shows the stark contrast between regional and worker-level effects. The black line reflects the traditional regional estimate: a one-percentage-point increase in the immigrant employment share reduces total native employment in the region by a substantial 0.87% after three years. However, the blue line tells a different story for workers employed at the time of immigration. It shows the effect on their probability of staying employed (i.e., the negative of the displacement effect). This probability falls by only 0.14 percentage points, and the effect disappears entirely after five years.

Figure 1: The impact of immigration on native employment

Notes: The figure displays coefficient estimates of the immigration shock from year-specific regressions. The immigration shock is the inflow of Czech workers between 1990 and 1992 as a share of total employment in 1990. The vertical dashed line indicates the timing of the shock. Source: Authors’ calculations based on Dustmann et al. (2025).

The large gap between the regional (-0.87%) and displacement (-0.14 pp.) effects is almost entirely explained by crowding-out. Immigration discourages native seeking work in affected municipalities, accounting for about 88% of the total decline in regional employment. The adjustment, therefore, is driven not by those employed at the time of immigration, but by those who would have entered the local labour market – yet now refrain from doing so.

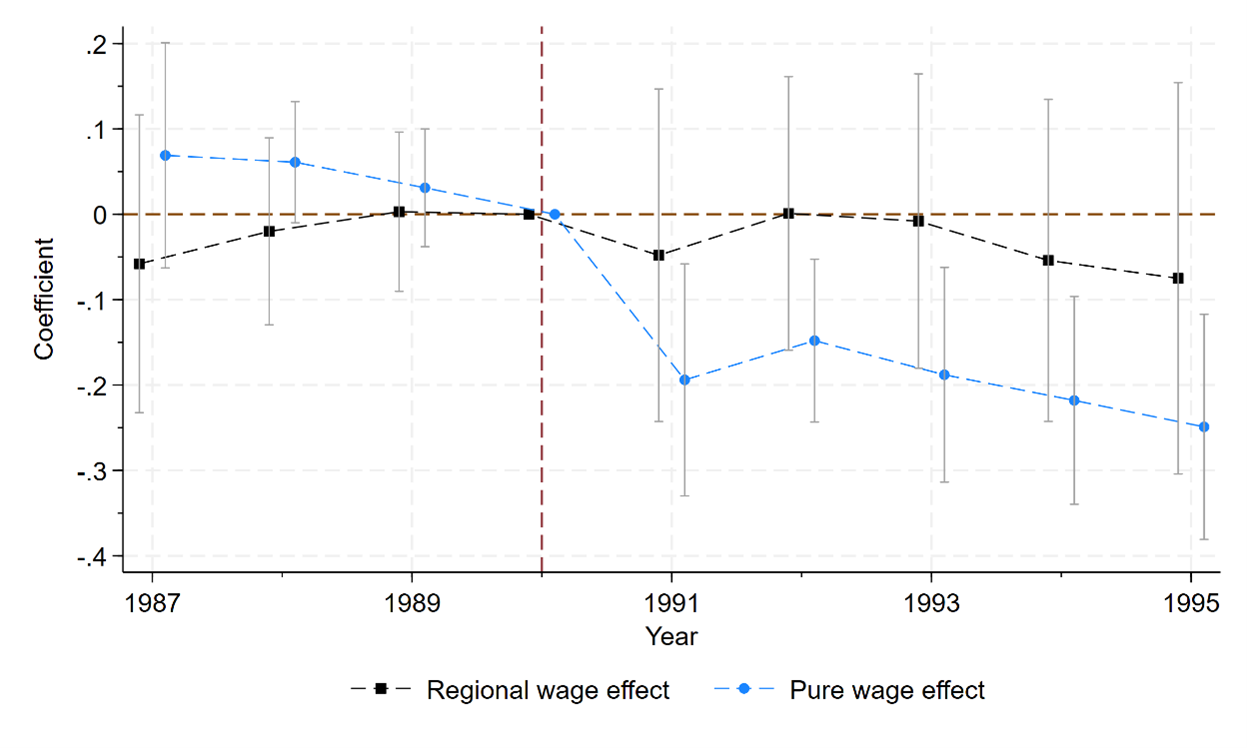

Wages: Compositional changes mask the pure wage effect

Figure 2 shows a similar divergence for wages. The regional wage effect (black line) is close to zero. But by tracking the same workers over time, we uncover the ‘pure’ wage effect (blue line). For natives who remained employed in the same region, a one-percentage-point increase in the immigrant share leads to a wage decrease of 0.19% after three years. Gauged against the overall wage growth of continuously employed natives of about 19 percent (26 percent) between 1990 and 1993 (1990 and 1995), this effect is nevertheless modest. This ‘pure’ wage effect is masked at the regional level because the immigration shock induces a change in the composition of the native workforce. The employment of low-wage native workers decreases, raising the average productivity and thus the average native wage. In our setting, this compositional change nearly offsets the negative pure wage effect, leading to a flat regional average wage.

Who is most affected?

Our analysis shows that the negative effects of the immigration shock are concentrated among specific, often vulnerable, groups. Older workers (aged 50 and above) are more likely to be displaced than younger ones. Workers without a job when the shock hits struggle more to return to the labour market and suffer larger wage losses than those who were employed. This finding that the non-employed are more affected is important. In our setting, employed workers, on the other hand, appear largely sheltered from the labour market consequences of immigration, experiencing only modest wage declines and limited displacement (see Figures 1 and 2).

Figure 2: The impact of immigration on native wages

Notes: See Figure 1

A new look at ‘upgrading’

Since Czech commuters mainly take jobs involving repetitive, rule-based tasks (manual/routine jobs), employment among natives in these jobs declines, while native employment in jobs that require problem-solving and decision-making (abstract jobs) remains stable. As a result, the share of natives working in more complex jobs increases. In other contexts, such a shift has been interpreted as evidence of native ‘upgrading’ in response to immigrant competition in manual jobs (see, e.g., Peri and Sparber 2009). Our data that follows individuals over time, however, allow us to test this directly. We find no evidence that native workers switch from repetitive-task jobs to more complex jobs. Instead, the shift in the regional job task structure is driven by the crowding-out effect, which is concentrated in repetitive-task jobs. However, we find evidence for a related effect: young natives who might have taken low-skilled jobs are more likely to enrol in Germany’s apprenticeship schemes, supporting the argument that low-skilled immigration raises native educational investments (Hunt 2017, Llull 2018).

Conclusion

Immigration affects places and workers in different ways. Our findings show that employed workers are surprisingly resilient to labour-supply shocks, but the adjustment costs may fall on others – especially new entrants and the non-employed – who in many studies are not explicitly considered. This insight extends beyond immigration; whether the shock arises from trade, automation, or other forces, distinguishing between impacts on places and impacts on people is essential for designing effective policy.

References

Borjas, George J. and Edo, Anthony (2025), “Gender, Selection into Employment and the Wage Impact of Immigration”, Journal of Labor Economics, forthcoming.

Bratsberg, Bernt and Raaum, Oddbjørn (2012), “Immigration and Wages: Evidence from Construction”, Economic Journal, 122(565): 1177–1205.

Card, David (2001), “Immigrant Inflows, Native Outflows, and the Local Labor Market Impacts of Higher Immigration”, Journal of Labor Economics, 19(1): 22–64.

Dustmann, Christian, Schönberg, Uta, and Stuhler, Jan (2016), “The Impact of Immigration: Why Do Studies Reach Such Different Results?”, Journal of Economic Perspectives, 30(4): 31–56.

Dustmann, Christian, Schönberg, Uta and Stuhler, Jan (2017), “Labor Supply Shocks, Native

Wages, and the Adjustment of Local Employment”, Quarterly Journal of Economics, 132(1): 435–483.

Dustmann, Christian, Otten, Sebastian, Schönberg, Uta and Stuhler, Jan (2025), “The Effects of Immigration on Places and People – Identification and Interpretation”, Journal of Labor Economics, forthcoming.

Hunt, Jennifer (2017), “The Impact of Immigration on the Educational Attainment of Natives”, Journal of Human Resources, 52(4): 1060–1118.

Llull, Joan (2018), “Immigration, Wages, and Education: A Labour Market Equilibrium Structural Model”, Review of Economic Studies, 85(3): 1852–1896.

National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine (2017), “The Economic and Fiscal Consequences of Immigration”. Editors: Blau, Francine D. & Mackie, Christopher National Academies Press.

Nedoncelle, Clément, Marchal, Léa, Aubry, Amandine and Héricourt, Jérôme (2025), “Does Immigration Affect Native Wages? A Meta-analysis”, CEPII Working Paper No. 2025-07.

Peri, Giovanni and Sparber, Chad (2009), “Task Specialization, Immigration and Wages”,

American Economic Journal: Applied Economics, 1(3): 135–169.