Short summary

Refugees typically have lower employment rates than natives and other migrants. One reason may be exposure to potentially traumatic events such as shelling, combat, torture, and the loss of close relatives. Such experiences can trigger severe trauma reactions that affect how people think, feel, and function in everyday life—and may therefore also affect their ability to work.

After Russia’s full-scale invasion of Ukraine in February 2022, Denmark received tens of thousands of Ukrainian refugees. Using Danish employment records linked to a survey conducted shortly after arrival, we examine whether early signs of post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD) help explain why some refugees integrate into the labor market slower than others.

Two years after arrival, Ukrainians with early signs of PTSD (29% of the cohort) are about 7 percentage points less likely to be employed than other Ukrainian refugees. Our results suggest that PTSD symptoms explain a meaningful share of the persistent refugee–native employment gap.

Key Findings

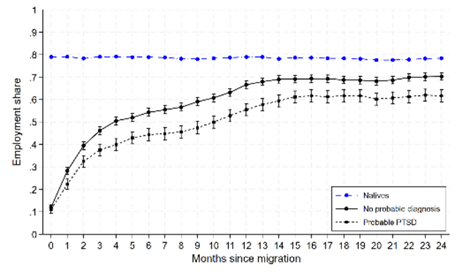

- Employment rates of Ukrainian refugees rise quickly after arrival, then level off after about one year. The employment gap between those with early signs of PTSD symptoms and other Ukrainian refugees also stops narrowing around the same time.

- Refugees with probable PTSD (while the survey instrument mirrors the diagnostic criteria used for PTSD, it is not a formal diagnosis and we therefore refer to it as probable PTSD) are 7-percentage points less likely to be employed two years after arrival.

- More severe symptoms are systematically linked to lower employment rates.

- The PTSD-related employment gap (~7 pp) is nearly twice as large as the employment premium associated with English proficiency (+4 pp) and is similar to the advantage of having been employed before displacement (+9 pp).

- Among those who do find work, PTSD is also associated with fewer hours worked per month, though not with lower hourly wages.

Relevance Today

Our study shows that PTSD is a measurable part of refugees’ labor-market integration. This suggests that psychological screening and early, symptom-focused support may complement existing integration policies. Today, this kind of care is mostly provided on a small scale by NGOs and volunteers. By contrast, public integration programs focus on language training, job-search assistance, on-the-job training, and financial incentives. These tools may work less well for refugees who struggle with trauma-related functional impairments. Integrating early psychological screening and targeted support into standard integration programs could help reduce persistent underemployment among refugees. More research is needed to test which approaches work, for whom, and at what cost.

Authors quote

“Mental health and integration outcomes are linked. Without identifying and addressing trauma reactions, we risk misunderstanding why some refugees struggle to find employment.”

Research summary

While refugees’ labor market integration improves rapidly early after settlement, research generally finds that a significant employment gap compared to natives and other migrants persists over time (see Brell, Dustmann, and Preston (2020) for an overview, and Schultz-Nielsen (2017) for the Danish case). Exposure to traumatic events and poorer mental health among refugees have long been discussed as potential explanations, but empirical evidence has been limited.

A key challenge is measurement. Administrative data on diagnoses or prescription drugs usage are not well suited for capturing trauma reactions shortly after displacement. They reflect treatment-seeking behavior and may partly capture mental health problems that emerge due to post-migration living difficulties. Similarly, existing surveys are usually from small convenience samples and not focused on the early period after displacement (e.g. Bryant et al, 2023). Hence, representative data on psychiatric symptoms due to exposure to traumatic events collected shortly after arrival is required to examine the link between trauma reactions and labor market integration of war refugees.

Our study combines validated survey instruments that measure probable PTSD among adult Ukrainians who arrived in Denmark in 2022 after Russia’s full-scale invasion (the Danish Refugee Cohort, DARECO) with labor-market trajectories from Danish administrative data. The prevalence of probable PTSD in this cohort is 29 percent (see also Karstoft, 2024).

Figure 1 shows that refugees with early PTSD symptoms have weaker employment trajectories after arrival. Employment rises steeply in the first months for all refugees, but the refugees with PTSD stay consistently below refugees without PTSD throughout the two-year window. After accounting for differences in education and household composition, a 7.4 percentage-point lower employment rate for those with probable PTSD persists. The difference emerges early and then stabilizes after roughly one year, rather than narrowing over time.

Figure 1: Employment share by months since arrival

Note: This figure shows monthly employment rates with 95% confidence intervals. For refugees, rates are plotted by months since arrival and by probable PTSD status. For native-born individuals, rates are plotted by months since May 2022, the modal arrival month for refugees.

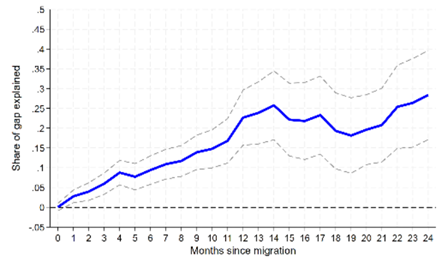

Figure 2 connects PTSD to the broader integration gap. It shows how much of the refugee–native employment gap may be attributed to probable PTSD. This share rises over the first year and reaches roughly one-quarter to one-third by the end of the second year. This pattern suggests that trauma-related symptoms are an important part of the persistent employment difference between refugees and natives.

Figure 2: Share of refugee-native employment gap explained by PTSD

Note: This figure plots the share of the refugee-native employment gap explained by PTSD (solid blue line) and 95% confidence intervals (dashed gray lines).

Probable PTSD is also associated with fewer hours worked, but not with lower hourly wages. In terms of magnitude, the employment disadvantage associated with PTSD is nearly twice as large as the employment premium linked to English proficiency (+4 pp) and comparable to the advantage associated with having been employed before displacement (+9 pp).

A key concern is that PTSD might simply reflect other disadvantages that also affect employment—such as education, family situation, work history before displacement, language skills, social networks, or where people are settled. To address this, we compare refugees with and without probable PTSD while adjusting step by step for these factors using the rich information in our DARECO survey. The PTSD–employment gap remains similar once we account for basic demographics and education. Our tests show that it is unlikely that unobserved differences are driving the result.

Policy Implications

Our study suggests that trauma reactions are a measurable and quantitatively important part of refugee integration. Existing integration policies emphasize language training, job search assistance, on-the-job training and financial incentives. These tools may be ineffective for refugees whose main barrier for employment are severe trauma reactions, because these tools do not address the binding constraint. Mental-health interventions that identify and alleviate trauma-related symptoms could therefore be an effective complement to existing labor-market integration programs.

Conclusion

Early signs of PTSD account for a significant share of the refugee-native employment gap among Ukrainian refugees in Denmark. After an initial phase of rapid economic integration, probable PTSD is associated with approximately 7 percentage points lower employment probability from one to two years after arrival. More research is needed to understand the extent to which our estimates generalize to other refugee populations and host countries and to evaluate which interventions are most effective.

References

Brell, Dustmann, and Preston. 2020. “The Labor Market Integration of Refugee Migrants in High-Income Countries.” Journal of Economic Perspectives 34(1), 94–121.

Byrant et al 2023 Bryant, R. A., A. Nickerson, N. Morina, and B. Liddell (2023). “Posttraumatic stress disorder in refugees.” Annual Review of Clinical Psychology 19(1), 413–436.

Karstoft, Korchakova, Koushede, Morton, Pedersen, Power, and Thøgersen. 2024. “(Complex) PTSD in Ukrainian refugees: Prevalence and association with acts of war in the Danish refugee cohort (DARECO).” Journal of Affective Disorders 366, 66–73.

Schultz-Nielsen 2017. „Labor market integration of refugees in Denmark.“ Nordic Economic Policy Review, 55 – 90.

Foged, Karstoft, and Zink (2025). “The majority of Ukrainians wish to stay in Denmark.” ROCKWOOL Foundation Analysis.

Disclaimer

The opinions and views expressed in this publication are those of the author(s) and do not necessarily reflect those of the ROCKWOOL Foundation Berlin (RFBerlin). While research disseminated through this series may address policy-relevant topics, RFBerlin, as an independent research institute, does not take institutional policy positions.

Publications in the RFBerlin Research Insights series may represent preliminary or ongoing work that has not been peer-reviewed. Readers are advised to consider the provisional nature of such research when citing or applying its findings.

These publications aim to make scientific work accessible to a broader audience and to encourage informed, research-based discussion. All materials are provided by the respective authors, who bear responsibility for appropriate attribution and rights clearance. While every effort has been made to ensure accuracy and proper acknowledgment, RFBerlin welcomes notifications of any concerns regarding authorship, citation, or intellectual property rights. Please contact RFBerlin to request corrections if needed.

Use of these materials for the development or training of artificial intelligence systems is strictly prohibited.