Short Summary

This study documents how a period of intense air pollution in the 1980s led to lasting health and economic costs. When East Germany sharply increased its use of lignite coal, air pollution rose near mining regions for nearly a decade. Because mobility was tightly restricted, affected populations could not relocate—allowing researchers to isolate the long-term effects of pollution. The results show that exposure in early life and adulthood translated into poorer health, shorter working lives, and lower earnings decades later.

Key Findings

- Air pollution rose by 19% in affected areas after 1982.

- Infant mortality increased by 9%, equal to one additional death per 1,000 births each year.

- Infants living near mines were 2.7% more likely to have low birth weight.

- Exposed individuals earn 3% lower wages and retire about two months earlier on average.

- They spend roughly 4.5 months less in employment over their working lives.

- Long-term health data show higher rates of asthma (+229%) and heart disease (+83%) decades after exposure.

Relevance Today

The findings show that pollution can leave a deep and lasting imprint on population health. Illnesses linked to air quality persist over the life cycle and reduce labor supply, productivity, and earnings. These results highlight the large and persistent social costs of air pollution and support policies that aim to reduce emissions early.

Reference

Based on RFBerlin Discussion Paper No. 85/25, The Long-Term Effects of Air Pollution on Health and Labor Market Outcomes: Evidence from Socialist East Germany by Moritz Lubczyk and Maria Waldinger (October 2025).

Research Summary

What are the effects of sustained air pollution exposure? This study provides clear evidence that exposure to polluted air can shape people’s health and economic prospects for decades. Using data from East Germany, where a sudden trade shock in 1982 led to a sharp and lasting increase in air pollution, the authors trace how early exposure affected health and labor outcomes up to forty years later. The results reveal that the damage from pollution extends well beyond immediate respiratory problems—it undermines long-term physical and economic well-being.

Lasting Impact of Air Pollution on Health and Productivity

Air pollution is one of the leading global health threats, linked to millions of premature deaths every year (World Health Organization 2024). While its short-term health effects are well established, much less is known about how sustained exposure affects people’s health and productivity later in life. Studying these long-term effects is difficult because people often move or adapt to changing environmental conditions (Deryugina and Reif 2023).

The historical experience of East Germany provides an opportunity to overcome this problem. When the Soviet Union abruptly reduced oil deliveries in 1982, the the government replaced them with locally mined lignite coal — a highly polluting energy source. The switch caused a sudden and persistent rise in air pollution near lignite mining regions and power plants. Because people could not easily relocate, the setting allows for a clean identification of long-term effects.

Key Findings

Short-Term Health Effects

Using newly digitized data on sulfur dioxide concentrations, together with historical birth and mortality records, the study first documents the immediate health effects of higher pollution:

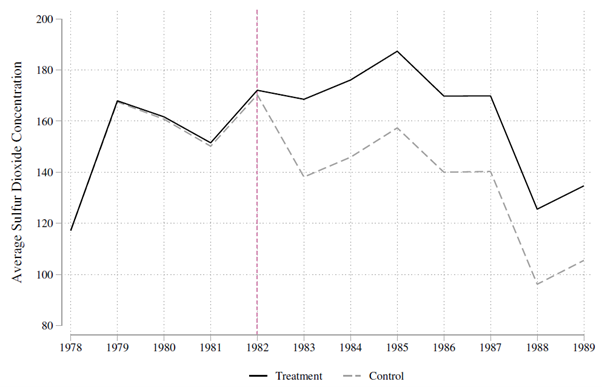

Sulfur dioxide levels increased by about 19% near lignite mines after 1982.

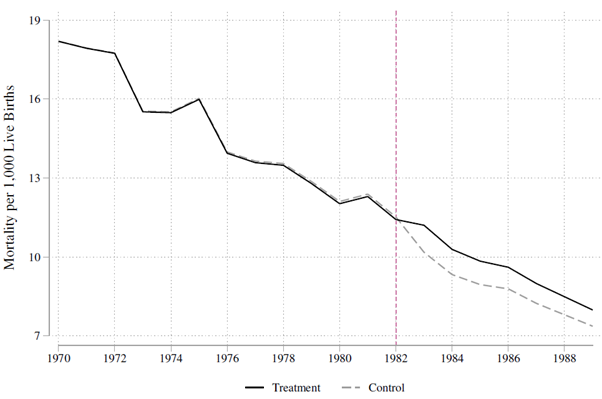

Infant mortality rose by 9%, equivalent to one extra death per 1,000 live births per year.

Low birth weight increased by 2.7%, with reductions most pronounced in the lower part of the birth weight distribution.

Elasticities of infant mortality with respect to air pollution are higher than in comparable settings where families can relocate (Currie, Neidell, and Schmieder 2009, Luechinger 2014, Knittel et al. 2016), suggesting that typical estimates may understate the actual health costs of pollution.

Figure 1. Sulfur Dioxide Concentration in Counties Close to Mines (Treatment) and Other Counties (Control), smoothed and centered means

Figure 2. Average Infant Mortality in Counties Close to Mines (Treatment) and Other Counties (Control), smoothed and centered means

Long-Term Health Effects

The most striking evidence concerns health many years later. Using panel data from the German Socio-Economic Panel, the study shows that people who lived in polluted areas during the 1980s report worse health outcomes even three decades later:

- They are more than twice as likely to suffer from asthma.

- They show an 83% higher incidence of heart disease, both major pollution-related illnesses.

- There is no difference in unrelated conditions such as diabetes or back pain. These results suggest that air pollution creates persistent damage to the respiratory and cardiovascular systems, with implications for healthcare demand and overall longevity.

Labor Market Consequences

Health deterioration translates into long-term economic effects. Administrative data covering more than six million East German workers show that individuals exposed to higher pollution before reunification experience weaker labor market outcomes over their lifetime:

- They spend 0.37 fewer years in employment and retire almost two months earlier.

- Average daily wages are about 3% lower, even after controlling for education, occupation, and industry.

A “movers” analysis, comparing people from polluted and non-polluted areas who later migrated to the same location, confirms these results and rules out local labor market differences as a confounding factor.

The authors estimate that lost employment after reunification alone represents a social cost of roughly 1% of German GDP in 1989, 10.98 billion Euros in 2015 prices.

Lessons for Policy

The evidence highlights that the full costs of air pollution unfold over decades. Beyond its immediate medical burden, pollution can reduce productivity and increase demand for healthcare. The findings suggest that improving air quality can yield benefits far into the future and that these benefits extend well beyond avoided deaths, including sustained gains in health and economic productivity.

For policymakers, the study underlines three key lessons:

- Long-term health monitoring is essential to understand the effects of pollution exposure.

- Preventive environmental policy, such as stricter emission limits and cleaner energy investments, creates lasting benefits that accumulate across generations.

- Environmental inequality matters: when specific populations are locked into polluted regions, the intergenerational costs of exposure become especially severe.

Conclusion

This study provides new evidence that air pollution can have long-lasting effects on both health and economic outcomes. Exposure to high levels of pollution in the 1980s led to worse health and lower labor force participation more than thirty years later. The findings underscore that air quality policy is not only a matter of environmental protection but also of long-term economic well-being and public health.

References

Alexander, Diane and Hannes Schwandt (2022): “The impact of car pollution on infant and child health: Evidence from emissions cheating,” The Review of Economic Studies, 89 (6), 2872–2910.

Chay, Kenneth Y and Michael Greenstone (2003): “The impact of air pollution on infant mortality: evidence from geographic variation in pollution shocks induced by a recession,” The Quarterly Journal of Economics, 118 (3), 1121–1167.

Currie, Janet and Matthew Neidell (2005): “Air pollution and infant health: what can we learn from California’s recent experience?” The Quarterly Journal of Economics, 120 (3), 1003–1030.

Currie, Janet, Matthew Neidell, and Johannes F Schmieder (2009): “Air pollution and infant health: Lessons from New Jersey,” Journal of Health Economics, 28 (3), 688–703.

Currie, Janet and Reed Walker (2011): “Traffic congestion and infant health: Evidence from E-ZPass,” American Economic Journal: Applied Economics, 3 (1), 65–90.

Deryugina, Tatyana, Garth Heutel, Nolan H Miller, David Molitor, and Julian Reif (2019): “The mortality and medical costs of air pollution: Evidence from changes in wind direction,” American Economic Review, 109 (12), 4178–4219.

Deryugina, Tatyana and Julian Reif (2023): “The long-run effect of air pollution on survival,” NBER WP, National Bureau of Economic Research.

Hanlon, W Walker (2020): “Coal smoke, city growth, and the costs of the industrial revolution,” The Economic Journal, 130 (626), 462–488.

Knittel, Christopher R, Douglas L Miller, and Nicholas J Sanders (2016): “Caution, drivers! Children present: Traffic, pollution, and infant health,” Review of Economics and Statistics, 98 (2), 350–366.

Luechinger, Simon (2014): “Air pollution and infant mortality: a natural experiment from power plant desulfurization,” Journal of Health Economics, 37, 219–231.

World Health Organization (2024): “Ambient (outdoor) air quality and health: Fact sheet,” WHO Fact Sheet, “The combined effects of ambient and household air pollution are associated with 6.7 million premature deaths annually.”

Disclaimer

The opinions and views expressed in this publication are those of the author(s) and do not necessarily reflect those of the ROCKWOOL Foundation Berlin (RFBerlin). While research disseminated through this series may address policy-relevant topics, RFBerlin, as an independent research institute, does not take institutional policy positions.

Publications in the RFBerlin Research Insights series may represent preliminary or ongoing work that has not been peer-reviewed. Readers are advised to consider the provisional nature of such research when citing or applying its findings.

These publications aim to make scientific work accessible to a broader audience and to encourage informed, research-based discussion. All materials are provided by the respective authors, who bear responsibility for appropriate attribution and rights clearance. While every effort has been made to ensure accuracy and proper acknowledgment, RFBerlin welcomes notifications of any concerns regarding authorship, citation, or intellectual property rights. Please contact RFBerlin to request corrections if needed.

Use of these materials for the development or training of artificial intelligence systems is strictly prohibited.