Authors

Christian Dustmann

(University College London & RFBerlin)

Chiara Lacava

(University of Naples Federico II)

Benjamin Schoefer

(University of California, Berkeley)

Chiara Giannetto

(University College London & RFBerlin)

Vincenzo Pezone

(LUISS Guido Carli)

Lorenzo Incoronato

(University of Naples Federico II, CSEF and RFBerlin)

Raffaele Saggio

(University of British Columbia)

Short summary

What happens when firms set wages outside of national agreements?

In many European countries, firms can under certain conditions opt out of national collective bargaining contracts and more flexibly negotiate wages with their workforce. Using data from Italy, this study shows that opt-outs reduce workers’ wages but increase their job retention and firm survival rates. These effects are especially pronounced in the more competitive regions. In labor markets where firms’ wage-setting power is high, instead, workers’ wage losses are larger and not compensated by employment gains.

Key Findings

- Workers experience a 2-3% wage decline when their firm opts out of national agreements, compared to similar workers not subject to opt outs.

- Employment stability rises: affected workers are 3–4 percentage points more likely to stay employed; this is largely driven by higher retention at the opting-out firm.

- Opting-out firms are more likely to remain in business than firms that do not opt out.

- Workers in the North of Italy experience small increases in earnings following opt-outs, as employment gains outweigh wage losses; in the South, instead, opt-outs do not imply higher worker retention, leading to a drop in net earnings.

- This result reflects different firm productivity and wage-setting power across space.

Relevance Today

European governments often debate reform of collective bargaining institutions to achieve higher flexibility for firms while preserving fair and equal working conditions. Our study shows that firms’ exits from centralized collective bargaining, while leading to wage losses, can benefit workers by improving labor market attachment; however, these positive effects for workers are not present in labor markets where firms have high wage-setting power.

Authors Quote

“Our study shows that firms’ opt-outs from centralized bargaining lead to cuts in labor costs but can also preserve jobs—especially in more productive and competitive regions. But when firms have labor market power, workers are likely to bear the costs of opt-outs.”

Reference: Opting Out of Centralized Collective Bargaining: Evidence from Italy, RFBerlin Discussion Paper (2025).

Research summary

Can more flexible collective bargaining institutions allow adjustment to economic shocks and regional labor market differences? What are the consequences of opting out from national wage-setting for firms and their workers? We explore these questions in the context of Italy, where firms have in recent years attempted to exit from a highly rigid and centralized system of industrial relations. Using detailed administrative data to identify firm opt-outs from national collective contracts into new agreements, often with lower wage floors, our study (Dustmann, Giannetto, Incoronato, Lacava, Pezone, Saggio and Schoefer, 2025) finds that firms that opt out pay lower wages, but at the same time increase retention of their employees and are more likely to remain in business. While workers seem to benefit overall from opt-outs, we highlight a clear regional divide: in Southern Italy, where firms have high wage-setting power, workers suffer wage losses that are not compensated by better job stability.

The pros and cons of collective bargaining decentralization

In most European countries, employer associations and unions negotiate collective bargaining agreements (CBAs) that determine minimum pay and other labor standards at the national level. While ensuring fair and equal conditions for workers across the national territory, these contracts may lead to distortions. As wages cannot typically be set below CBA-specific floors, firms facing unexpected shocks and unable to cut labor costs may need to lay off their workers. Moreover, wage floors set nationally may be too high for firms operating in low-productivity areas (Boeri, Ichino, Moretti and Posch, 2021). Researchers and policymakers have long debated possible decentralization, for example, by allowing firms to opt out of centralized CBAs and negotiate locally (Dustmann, Fitzenberger, Schoenberg and Spitz-Oener, 2014; Calmfors and Driffill, 1988; OECD, 2019). While opt-outs could enhance labor market flexibility and competitiveness, they may also lead to losses for workers. Yet these effects are still not well-documented empirically, primarily because of the challenges in observing opt-outs in the data.

Lessons from the Italian experience

To investigate the effects of firms’ opt-outs from centralized collective bargaining, this paper takes advantage of recent developments in Italy, focusing on two decentralization episodes that occurred in the 2010s. First, a group of large retailers (Federdistribuzione, FD) left their national employer federation in 2011 to negotiate separate terms with unions. Second, many firms have opted out of national CBAs, negotiated by the main unions to adopt so-called “pirate” agreements – contracts with smaller unions setting lower wage floors and more flexible working conditions compared to national CBAs (Lucifora and Vigani, 2021). The empirical analysis leverages unique administrative data that link each Italian worker to their firm and the exact CBA applied, allowing for the precise identification of opt-outs in the data. The research design, harmonized across the two opt-out events, compares workers subject to opt-outs to similar workers who do not experience an opt-out and instead continue to be employed under a national CBA, before and after the opt-out decision.

The impact of opt-outs on workers and firms

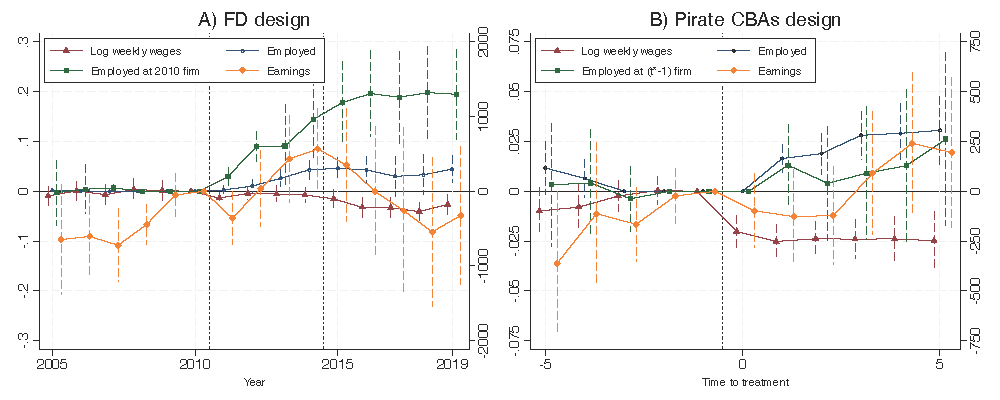

The empirical findings are clear and consistent across the two opt-out episodes described above. We summarize them in Figure 1, where Panel A shows results for the mass retailers (FD) opting-out and Panel B for the pirate agreements. The outcomes we focus on are workers’ wages (triangles, red), employment probability (circles, blue), retention at the original firm (squares, green), and labor earnings (diamonds, yellow). First, workers whose firm decides to opt out experience wage losses compared to similar workers who are still covered by centralized CBAs. We estimate these losses at 2-3%, which appear quickly after the opt-out event and persist for several years afterward. This wage decline is concentrated among workers who remain at the opting-out firm. Second, we notice a positive effect on workers’ employment stability. Affected workers are 3–4 percentage points more likely to remain employed in the years after the opt-out. Much of this improvement in labor market attachment comes from higher retention at the opting-out firm. The wage and employment effects roughly balance each other, implying null effects on labor earnings. Firm-level outcomes mirror the worker results: opting-out firms lower their wage bill by approximately 3% and exhibit a slight increase in short-run survival probabilities compared to similar firms that do not opt out.

Figure 1.

Note:The figure displays coefficient estimates from event-study regressions comparing workers subject to opt-outs to workers that are still covered by centralized CBAs. Comparisons are made between workers with similar observed characteristics. Panel A shows results for the mass retailers (Federdistribuzione, FD) opt-out, and Panel B for pirate agreements opt-outs. Log weekly wages are calculated for the dominant job, i.e., the job with most weeks worked in a given year. Employed is an indicator equal to 1 if a given worker in a given year has at least one day of employment, as recorded by social security. Employed at the 2010 firm or (t*−1) firm is an indicator equal to 1 if a given worker in a given year is employed by their 2010 employer or their t*−1 employer (t* denotes the year of transition to a pirate agreement). Earnings are calculated as the sum of labor earnings obtained by a worker in a given year and are expressed in 2010 euros. Coefficients for Log weekly wages, Employment, and Employment at the 2010 or (t*−1) Firm are displayed on the left vertical axis. Coefficients for Earnings are displayed on the right vertical axis.

Mechanisms and regional differences

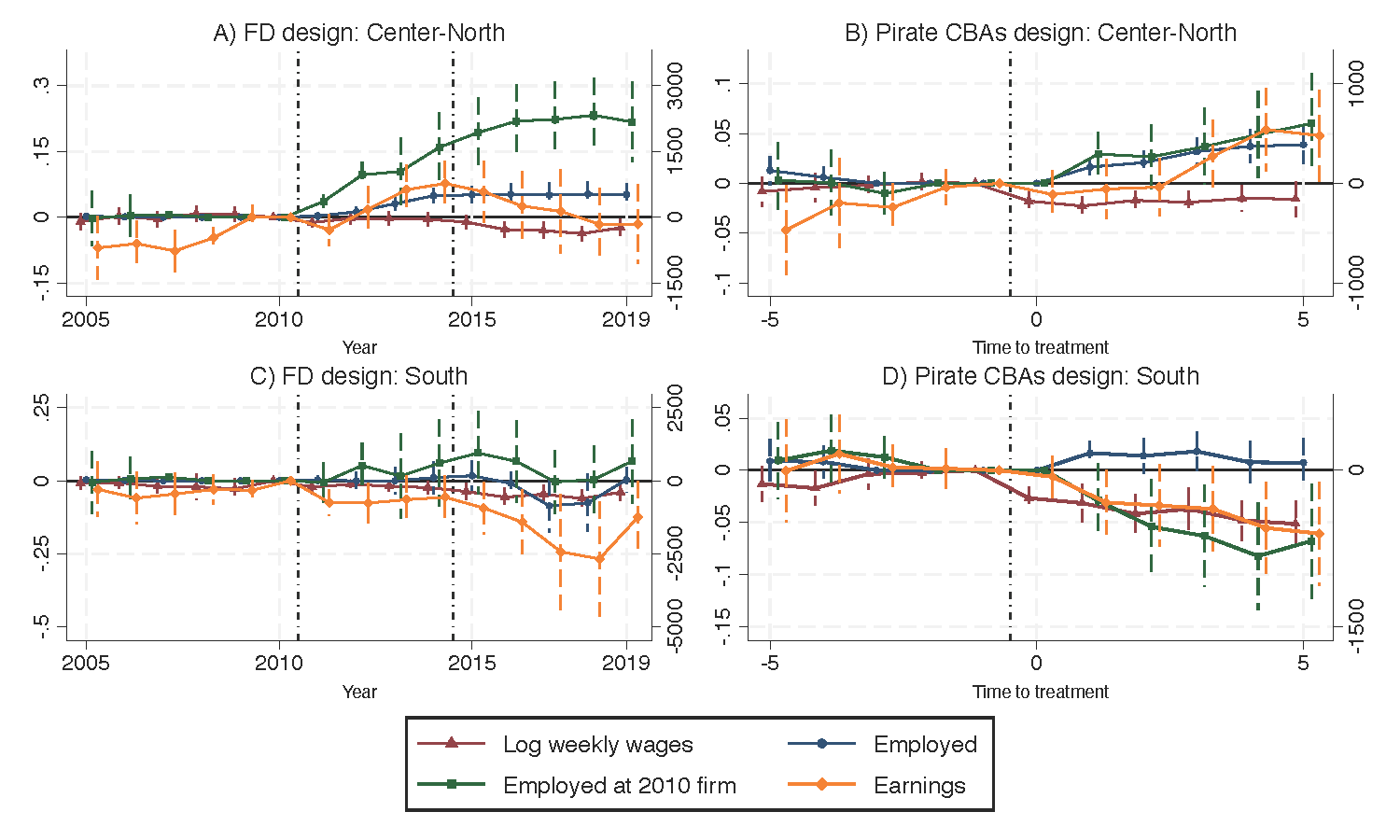

The evidence of relative wage drops and employment increases suggests that standard labor-demand channels are at play behind opt-outs: when firms are no longer bound by national wage floors, they can reduce pay instead of resorting to layoffs or closures. As a result, worker earnings are unaffected by opt-outs as higher job retention probabilities offset wage losses. As shown in Figure 2, however, these aggregate results mask regional differences. We replicate the analysis shown in Figure 1 but separate between workers in Northern (Panels A-B) versus Southern (Panels C-D) Italy, for each opt-out event. This analysis reveals that the previous baseline effects are particularly pronounced in Italy’s north. There, firms tend to be more productive and face more competitive labor markets; higher flexibility through opting out allows firms to reduce wages modestly and expand or preserve employment. This leads to even slightly positive effects on worker earnings in the North. In the South, where firms are typically less productive and have higher wage-setting power, opting out leads instead to larger wage cuts and little or no gain in employment.

Figure 2.

Note: The figure displays coefficient estimates from event-study regressions comparing workers subject to opt-outs to workers that are still covered by centralized CBAs. Comparisons are made between workers with similar observed characteristics. Regressions are run separately for workers employed in the Center-North (Panels A and B) and South (Panels C and D) of Italy in the year before the opt-out. Panels A and C show results for the mass retailers (Federdistribuzione, FD) opt-out, and Panels B and D for pirate agreements opt-outs. Log weekly wages are calculated for the dominant job, i.e., the job with most weeks worked in a given year. Employed is an indicator equal to 1 if a given worker in a given year has at least one day of employment, as recorded by social security. Employed at the 2010 firm or (t−1) firm is an indicator equal to 1 if a given worker in a given year is employed by their 2010 employer or their t*−1 employer (t* denotes the year of transition to a pirate agreement). Earnings are calculated as the sum of labor earnings obtained by a worker in a given year and are expressed in 2010 euros. Coefficients for Log weekly wages, Employment, and Employment at the 2010 or (t*−1) Firm are displayed on the left vertical axis. Coefficients for Earnings are displayed on the right vertical axis.

Lessons for policy

The debate about wage-setting decentralization is a longstanding, but still unresolved one primarily due to a lack of robust empirical evidence. This paper sheds light on the possible consequences of decentralization through firm opt-outs from national CBAs. Results underscore that increased flexibility could improve labor market competitiveness and allow firms to reduce labor costs while preserving jobs. However, these conclusions are unlikely to hold in labor markets where firms have high wage-setting power and may mark down wages without increasing employment. In this case, a centralized collective bargaining set-up may curb firms’ market power and benefit workers.

Conclusions

This study provides novel empirical evidence on the effects of collective bargaining decentralization on affected workers and firms. Focusing on recent developments in Italy, and leveraging rich worker-firm data allowing to directly observe opt-outs, the analysis documents how firms opting out of centralized collective bargaining reduce wages but are more likely to survive and retain workers. For workers in Northern Italy, the increase in job retention more than compensates for the wage losses. In the South, instead, workers suffer a drop in earnings following opt-outs. These findings highlight that the impact of decentralization may depend critically on local productivity and the wage-setting power of firms. Future research will provide a more comprehensive picture of the aggregate, market-level impacts of opting out and collective bargaining decentralization.

References

Boeri, Tito, Andrea Ichino, Enrico Moretti, and Johanna Posch, “Wage Equalization and Regional Misallocation: Evidence from Italian and German Provinces,” Journal of the European Economic Association, 2021,19 (6), 3249–3292.

Calmfors, Lars, and John Driffill, “Bargaining Structure, Corporatism and Macroeconomic Performance,” Economic Policy, 1988, 3 (6), 14–61.

Dustmann, Christian, Bernd Fitzenberger, Uta Schönberg, and Alexandra Spitz-Oener, “From Sick Man of Europe to Economic Superstar: Germany’s Resurgent Economy,” Journal of Economic Perspectives, 2014, 28 (1): 167–88.

Dustmann, Christian, Chiara Giannetto, Lorenzo Incoronato, Chiara Lacava, Vincenzo Pezone, Raffaele Saggio, and

Benjamin Schoefer, “Opting Out of Centralized Collective Bargaining: Evidence from Italy,” RFBerlin Discussion Paper, 2025, No. 43/25.

Lucifora, Claudio, and Daria Vigani, “Losing Control? Unions’ Representativeness, Pirate Collective Agreements, and Wages,” Industrial Relations: A Journal of Economy and Society, 2021, 60(2), 188-218.

OECD, “Negotiating Our Way Up,” 2019, p.270.