Short summary

As populations age, keeping people in work later in life has become an economic necessity. Yet many older job seekers still face substantial barriers to reemployment. In the United States and Europe, employers are prohibited from stating age requirements in job advertisements, but a large body of evidence shows that age discrimination in hiring remains widespread. China provides a rare and informative setting to study this issue. There, employers can legally specify age limits in job ads, making age-based screening visible at the very first stage of recruitment. In our paper, we ask two central questions: when do firms choose to impose age caps in job advertisements, and how do job seekers respond to these restrictions?

Key Findings

- Nearly half of job ads specify an age range, and most of these limits exclude older applicants. About 80% of job ads with age restrictions exclude applicants older than 40.

- Age caps are more common in high-intensity, lower-skill jobs and when screening applicants is costly. They are also less common when employers face strong competition for workers.

- Explicit age caps in job descriptions emphasize learning and personal growth, which often appeals more to younger applicants.

- Age limits influence who applies: When a posting sets a maximum age of 40, it attracts more applicants aged 23 or younger and deters applicants aged 27 and above.

- Postings with age caps receive fewer applications from university educated candidates, suggesting a lower skilled applicant pool on average.

- Applicants do not fully comply with age caps, and noncompliance is higher for vacancies with higher wages or higher skill requirements.

Relevance Today

In rapidly ageing economies, explicit age caps can discourage job search among older and mid-career workers and reduce the skill level of the applicant pool. These effects matter for labor market efficiency and for policies in China and elsewhere that aim to keep older workers attached to the labor force.

Authors quote

“Explicit age requirements in job ads are not only widespread, but also systematically linked to who applies, the skill mix of applicants, and the types of jobs and employers that rely on them. In ageing labor markets, reducing reliance on age-based screening may require a combination of stronger enforcement of labor standards and support for lifelong learning and mid-career training.”

Research summary

Age discrimination in hiring is widespread, but it is usually invisible because most countries ban employers from stating age requirements in job ads. China provides a rare exception: employers can openly list age ranges online, letting us observe age screening at the very first stage of recruitment. We find that firms are more likely to impose age caps on physically demanding, lower-skill, or costly-to-fill jobs, and in markets with weaker competition. These caps attract younger applicants and discourage middle-aged and older workers, though some older candidates still apply to high-wage or high-skill positions. By comparing similar job postings that do and do not include age limits, we can directly see how these caps shape who applies and who does not.

Many economies are ageing, which makes it more important to keep people at work later in life. However, evidence from the literature continues to show that older workers face significantly longer unemployment spells (Johnson and Neumark, 1997; Button and Neumark, 2014, 2022), fewer training opportunities (Perron, 2021), and most significantly, hiring disadvantages (Riach and Rich, 2002; Lahey, 2008; Riach and Rich, 2010; Neumark, 2012; Baert et al., 2016; Carlsson and Eriksson, 2019; Neumark et al., 2019a; Yu et al., 2025), raising concerns about fairness, productivity, and the financial sustainability of pension systems.

In most high income countries, however, employers cannot openly state age requirements in job ads, so age discrimination is harder to observe at the earliest stage of recruitment and harder to link to specific job features. China provides a useful contrast because online job postings can explicitly list age ranges. This setting makes age screening visible and measurable in a way that is rare elsewhere, allowing the paper to speak directly to two questions at the heart of global debates: when firms choose to screen by age, and how job seekers respond when they see an age barrier up front.

The analysis uses nearly 7.7 million job postings from a major Chinese online job board posted between November 2018 and April 2019. In addition to the full vacancy text and standard job attributes, the data include a dedicated age requirement field and vacancy-level group characteristics of applicants, including the age and education distribution of people who applied.

Key findings

How common are explicit age caps, and where do they come from?

Nearly half of job ads specify an age range, and most of these caps are set young. Around 80% of ads with age limits exclude applicants above 40. The pattern also looks firm-specific. Even within the same industry and local occupation market, some firms almost always use age caps while others rarely do, rather than firms switching caps on and off across different vacancies.

Why do firms age discriminate?

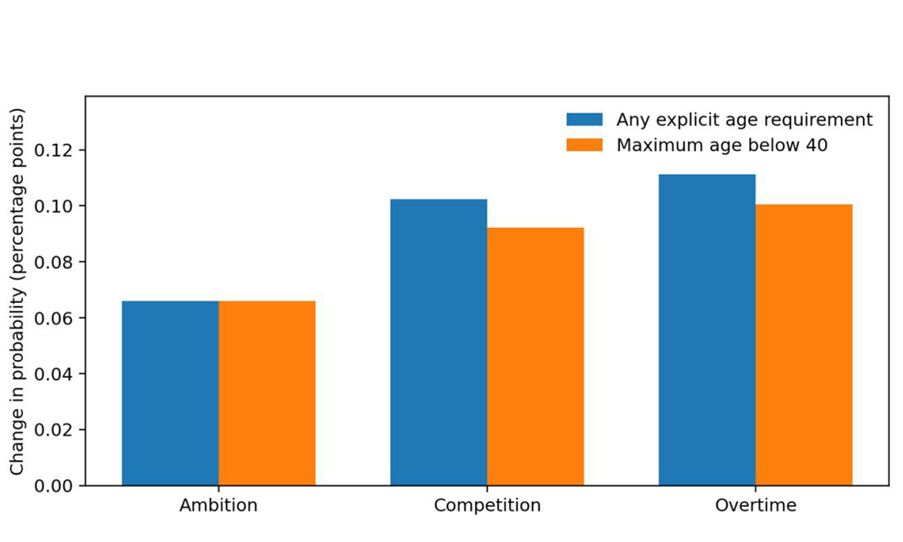

Age caps are closely tied to high work intensity job attributes. Job postings mentioning ambition, competition, or overtime are 6 to 11 percentage points more likely to include age requirements and set age caps below 40. This implies, for example, that ads mentioning overtime are 23% and 31% more likely to include age caps and exclude older workers above the age of 40. In other words, employers appear more likely to impose age limits in jobs that advertise pressure, long hours, or intense environments because they hold stereotypes that older workers, for example due to family responsibilities, are less able or willing to overwork. Even when older applicants believe they can meet these demands and still apply, employers may expect that evaluating their fit requires more effort, which makes screening feel more costly and increases the incentive to state an age preference up front and exclude older workers.

Figure 1. Work intensity keywords and explicit age screening (percentage point changes). The bars report how the probability that a vacancy states an age requirement changes when the posting contains keywords linked to ambition, competition, or overtime. Source: Table 5 of Luo, Zhang, and Zhang (2025), preferred specifications.

Vacancies with high skill requirements are also less likely to post explicit age caps. The paper shows that postings requiring a university degree or emphasizing cognitive skills are less likely to state an age range or to set a tight maximum age. This pattern aligns with the trade off highlighted in Kuhn and Shen (2013): when firms want the best candidate, narrowing the pool with a blunt demographic filter is less attractive. By contrast, age caps are more common where hiring appears more costly, proxied by a larger expected applicant pool, and where local labor markets are less competitive.

How do applicants respond?

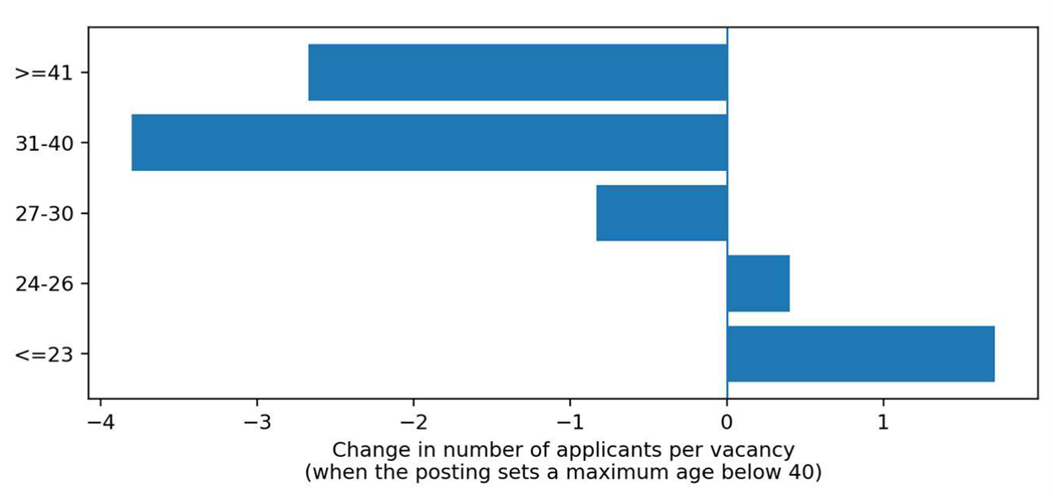

Age caps change who applies. When a job sets a maximum age of 40 or younger, applications from workers aged 23 or younger rise, while applications from older groups fall sharply. Importantly, even applicants aged 27 to 30, who are typically still eligible under such caps, apply less. This suggests that they read a tight cap as a strong preference for very young workers and may avoid jobs where they expect lower chances, a workplace culture that is not welcoming to older staff, or weaker job security as they age.

Figure 2. Applicant responses to maximum age below 40 (change in applicants per vacancy). The bars show how the number of applicants in each age group changes when a posting sets a maximum age below 40. Source: Table 2 of Luo, Zhang, and Zhang (2025).

Age caps also change the skill composition of applicants. Using education as a simple indicator of skill, the paper shows that postings with age limits attract fewer university educated applicants. Specifically, an explicit age requirement is linked to about 2.3 fewer university educated applicants per vacancy, and a maximum age below 40 is linked to about 5 fewer. This highlights a trade off: firms can attract younger applicants by posting age caps, but they may lose high skilled applicants at the same time.

Applicants do not fully comply with posted age limits. Compliance is high on average, around 85% for vacancies capped at 40, but it falls when jobs are more attractive. Higher wages and high skilled are associated with lower compliance. This suggests that some older applicants still apply when the job looks worth it, and that job seekers treat age caps as a signal about employer preferences rather than a strict rule that strictly binds.

Conclusion

This paper uses a unique setting where employers can openly state age limits in job ads to document how common explicit age caps are and how they shape the early stages of hiring. The main takeaway is that age requirements are not only widespread, but also systematically linked to who applies, the skill mix of applicants, and the types of jobs and employers that rely on them. These patterns suggest that applicants treat age caps as a strong signal that employers prefer very young workers.

Several questions remain. How do workers respond over time when age limits appear early in their careers, for example by changing jobs or upgrading skills? If explicit age caps are restricted, how to prevent employers from switching to subtler ways of signaling a preference for younger workers? And which policy tools, from age neutral screening to stronger labor standards and practical retraining, can reduce age barriers without making hiring harder for firms?

References

David Neumark. Detecting discrimination in audit and correspondence studies. Journal of Human Resources, 47(4):1128–1157, 2012.

David Neumark. Age discrimination in hiring: Evidence from age-blind versus non-age-blind hiring procedures. Journal of Human Resources, 59(1):1–34, 2024.

David Neumark, Ian Burn, and Patrick Button. Is it harder for older workers to find jobs? New and improved evidence from a field experiment. Journal of Political Economy, 127(2):922–970, 2019a.

Magnus Carlsson and Stefan Eriksson. Age discrimination in hiring decisions: Evidence from a field experiment in the labor market. Labour Economics, 59:173–183, 2019.

Patrick Button and David Neumark. Did age discrimination protections help older workers weather the great recession? Journal of Policy Analysis and Management, 33(3):566–601, 2014.

Patrick Button and David Neumark. Age discrimination’s challenge to the American economy. NBER Reporter, (3):8–11, 2022.

Peter A Riach and Judith Rich. Field experiments of discrimination in the market place. The Economic Journal, 112(483):F480–F518, 2002.

Peter A Riach and Judith Rich. An experimental investigation of age discrimination in the English labor market. Annals of Economics and Statistics, pages 169–185, 2010.

Peter Kuhn and Kailing Shen. Gender discrimination in job ads: Evidence from China. The Quarterly Journal of Economics, 128(1):287–336, 2013.

Richard W Johnson and David Neumark. Age discrimination, job separations, and employment status of older workers: Evidence from self-reports. The Journal of Human Resources, 32(4):779, 1997.

Stijn Baert, Jennifer Norga, Yannick Thuy, and Marieke Van Hecke. Getting grey hairs in the labour market. an alternative experiment on age discrimination. Journal of Economic Psychology, 57:86–101, 2016.

Disclaimer

The opinions and views expressed in this publication are those of the author(s) and do not necessarily reflect those of the ROCKWOOL Foundation Berlin (RFBerlin). While research disseminated through this series may address policy-relevant topics, RFBerlin, as an independent research institute, does not take institutional policy positions.

Publications in the RFBerlin Research Insights series may represent preliminary or ongoing work that has not been peer-reviewed. Readers are advised to consider the provisional nature of such research when citing or applying its findings.

These publications aim to make scientific work accessible to a broader audience and to encourage informed, research-based discussion. All materials are provided by the respective authors, who bear responsibility for appropriate attribution and rights clearance. While every effort has been made to ensure accuracy and proper acknowledgment, RFBerlin welcomes notifications of any concerns regarding authorship, citation, or intellectual property rights. Please contact RFBerlin to request corrections if needed.

Use of these materials for the development or training of artificial intelligence systems is strictly prohibited.